|

|

A LOOK THROUGH THE JUDAS

HOLE[1]

Significance of the topic.

The Imperial Russian prison-and-exile system exerted a profound influence on

the empire's development, culture, politics, social and natural sciences.

Russia's history cannot be properly understood without taking prison and

exile into consideration.

1) Geography and demography. If one

were to exhibit Imperial-Russian or Soviet-era Siberia, for example, such an

undertaking could not ignore one simple fact: Siberia was for many years the

tsars' preferred dumping ground for criminals and those whose politics were

perceived by the authorities as a threat, potential or real. Much as Britain

used convicts to settle Australia, and France - New Caledonia, so too did

Russia use criminal and political exiles in an attempt to populate the Far

North, Siberia and Sakhalin. By 1662 more than one in every ten people in

Siberia were exiles,[2] and by 1900, when criminal exile to Siberia was

finally and drastically curtailed, that percentage had reached considerably

higher. The country's demography underwent a radical change in the short

span of a century, in large part due to her prisons and places of exile. It

was the political exiles that brought Russian culture and civilization to

that area, and to a considerable extent, it was prison labor that built the

roads and railroads and opened up its expanses.

2) Political history. Any exhibit of

Soviet material that touches upon the Soviet Gulag, say, or presents a

thematic study of the Communist Party or this or that Soviet leader, must of

necessity take the tsarist prison and exile system into account. Many of

those who did the imprisoning during the Soviet regime had themselves been

incarcerated and exiled under Alexander III and Nicholas II, and they

learned their lessons all too well. For instance, the 140 members who

attended the 1905 Congress of the Socialist-Democratic Party in Stockholm

had between them already spent a total of 138+ years in prison and another

148+ years in exile. "If we take into account the fact that the 140 members

had spent a total of 942 years in the social-democratic movement, we shall

see that the periods spent in prison and exile represented about one-third

of the time spent actively in the party."[3] Here is just a short list of

only the top few tiers of the Soviet pantheon, those who lived to see

October 1917 and serve in the new government:

- V.I. Lenin - prison (St.

Petersburg Preliminary Detention Facility - SPB PDF) and internal exile;

- L. Trotsky - prison (SPB PDF) and

internal exile (Ust' Kut, Obdorsk);

- I.V. Stalin (Dzhugashvili) - prison (Bailov

Prison in Baku, SPB PDF), internal exile (Solvychegodsk and Vologda);

- F.E. Dzerz'hinsky, the father of the

Soviet security police - prison (Aleksandrovskiy Central, Orel Central)

and internal exile (Nolinsk and Kay in Vyatka Province, Verkholensk and

Kansk in Siberia);[4]

- M.V. Frunze - prison (Vladimir) and

internal exile (Irkutsk Province);[5]

- M.I. Kalinin - prison (SPB PDF) and

internal exile (Povenets, Olonets Province);[6]

- L. B. Kamenev - prison (SPB PDF),

internal exile (Tiflis, Eastern Siberia);[7]

- S.V. Kosior - prison (Moscow),

internal exile (Irkutsk and Yekaterinoslav Provinces);[8]

- V.V. Kuybyshev - prison (Omsk and

Tomsk), internal exile (Kainsk, Kolpashevo, Tomsk Province);[9]

- M.I. Latsis (Sudrabs) - prison, exile

to Irkutsk;[10]

- V.M. Molotov - prison and internal

exile;

- G.K. Ordzhonikidze - prison (Shlissel'burg)

and internal exile (Yenisey Province, Olekminsk (Yakutsk Oblast'));[11]

- G.L. Pyatakov - internal exile;

- Ya.E. Rudzutak - prison (Riga, Moscow

(Butyrka));[12]

- A.I. Rykov - prison (Moscow),

internal exile (Arkhangel'sk, Samara, Saratov, Narymsk Territory);[13]

- Ya.M. Sverdlov - prison, internal

exile (Narymsk, Kolpashevo, Tomsk Province, among others);[14]

- Tomskiy, M.P. - prison (Revel',

Moscow (Butyrka)), internal exile (Narymsk Territory);[15]

- M.A. Trilisser - prison (Shlissel'burg),

exile (Siberia);[16]

- M.S. Uritsky - internal exile (Olekminsk

(Yakutsk Oblast'), Vologda and Arkhangel'sk);

- K.Ye. Voroshilov - prison ("Kresty, "Arkhangel'sk),

internal exile (Arkhangel'sk Province, Perm' Province);[17]

- V.V. Vorovskiy - internal exile (Vyatka

Province);

- G.G. Yagoda - internal exile (Simbirsk).[18]

Nor was it just the coup leaders whose

experiences in prison influenced their outlook. As Vladimir

Vilenskiy-Sibiryakov pointed out in 1925,

"The role played by the prison, hard-labor

and exile system after 1905 was exceptionally important for the subsequent

development of the Russian revolutionary movement. In the past, tsarist

prisons were places where revolutionaries were entombed, places of the

strictest isolation, but after the first Russian revolution those tsarist

prisons turned into a huge cauldron of revolution, where great numbers of

professional revolutionary cadres were readied. The Revolution of 1905 drew

in the broad masses of workers and peasants; tens of thousands of them

poured into tsardom�s jails as its prisoners after the collapse of the first

Russian revolution." [19]

3) Culture: the arts and literature.

Russia's arts and literature have been greatly affected by the Russian

prison system. There is a vast corpus of prison and exile memoirs, but

whether the authors wrote from personal experience on the wrong side of the

bars - Dostoevsky's Notes from the House of the Dead, Crime and Punishment,

Maksim Gorky and D.I. Pisarev (imprisoned in the Trubetskoy Bastion of the

Peter-and-Paul Fortress),[20] M.Ye. Saltykov-Shchedrin and V.G. Korolenko

(both in Vyatka exile)[21] - or from tours on the better side of the cell

doors - Anton Chekhov, V. Doroshevich (Sakhalin), S. Maksimov (Katorga

Imperii), A. Svirskiy (Kazennyy dom) - the effect they had on contemporary

public opinion was considerable. They also exposed corruption in provincial

administration and mocked the red tape that afflicted everyone. Some of

their works are still required reading at colleges and universities.

From the authors to the painters, then. The

so-called "Society of Wandering Exhibitions," the members of which were

referred to as "The Wanderers" - I.Ye. Repin, N.A. Kasatkin, V.G. Perov,

V.Ye. Makovskiy, V.I. Yakobi, and N.A. Yaroshenko, to name just some of them

- produced works on the prison and court themes. Lesser lights did as well:

Zarin, V. Shereshevsky, K. Lebedev, Ye.M. Svarog, and many others. After the

Soviets came to power, drawing and painting the theme of tsarist oppression

became a cottage industry hitched to the propaganda cart.

There is also a considerable body of

prison-related Russian music, most of it surviving in songs. In 1935, for

instance, the State Musical Publishing House and the Folklore Section of the

Soviet Academy of Sciences issued the "Collection of Revolutionary Songs in

Russia," a part of which was devoted to the prisons. "Arestant," "Uznik,"

"Po pyl'noy doroge telega nesetsya," "Aleksandrovskiy tsentral," and on, and

on.[22] These lyrics survived into the Gulag period and were "recycled" by

the zeks in modified form; some survived in the original version.

4) The natural and social sciences:

anthropology, biology, botany, geology, sociology, etc. Even when the

authors weren't writing about their own situation, they were describing,

often for the first time anywhere, the inhabitants, history and culture of

the remote areas in which they had been imprisoned or exiled. The

statistical and natural sciences were considerably advanced in these remote

areas when the exiles arrived and began keeping records on everything from

temperature to the price of cattle.

Censorship. And we have not even

touched upon the field of court, police and prison censorship itself yet.

Here, we can watch the politicals attempting to communicate through the

mail, and the authorities looking for anything suspicious in hopes of using

it against one or both of the correspondents. This was a battle of chemistry

(secret inks and reagents), euphemisms, dots above letters, restrictions on

writing, handwriting analysis, cell searches and arbitrary mail delays, all

waged under the rubric of "mail censorship." Since political prisoners were

almost by definition literate, it is their mail we see the most of in our

collections (the overwhelming majority of criminals were illiterate or

semi-literate), and precisely because the great majority of people sending

and receiving mail in this field were politicals, prison mail mirrors the

great ideological struggles of the 1870s to 1917 like no other. Much of the

correspondence in this exhibit was written by politicals and censored by the

authorities: the police, prosecutors, investigators, wardens, and military

officers.

Rarity of the material. Insofar as

prison, court and police censor marks are concerned, there are a few that

are relatively common, including most Shlissel'burg Hard-Labor Prison and

St. Petersburg Preliminary Detention Facility handstamps, and some St.

Petersburg and Moscow court markings. Everything else ranges from rare to

only one example recorded. For usages, mail between prisoners is extremely

rare, as is package mail, correspondence by telegram, registered mail from

prisoners, mail between convicts and foreign addressees, mail to and from

criminals, and forwarded mail.

Production and layout of the exhibit.

This exhibit was produced with a PowerPoint program and Microsoft Windows

98.

Outline of the Exhibit

I. The authorities - the police and

the Ministries of Internal Affairs and Justice:

- Third Section;

- Ministry of Internal Affairs;

- Department of State Police;

- Department of Police (the "Okhranka");

- Independent Corps of Gendarmes:

- Major directorates;

- Provincial directorates;

- Special directorates;

- Railroad directorates;

- Provincial governors;

- Regular police and adjuncts:

- City police administrations;

- City precinct police;

- City precinct police inspectors;

- Rural district police chiefs;

- Rural precinct police chiefs;

- Zemstvo chiefs;

- Volost' foremen;

- Main Prison Directorate:

- Resubordination;

- Prison Inspectorate;

- Jurisprudential establishments:

- Governing Senate;

- Ministry of Justice:

- Superior courts;

- Circuit courts, "Hauptman"

courts;

- Justices of the peace;

- Rural district courts;

- Volost' and "gmina" courts;

- Zemstvo courts;

- Ministry of War military courts.

II. The prisoners - how they went

from citizen to prisoner or exile:

- Physical surveillance;

- "Procedural"

surveillance;

- Clandestine mail surveillance;

- Surveillance abroad - Paris Agentura;

- Police search;

- Arrest;

- Trial preparation;

- Conviction and sentencing;

- Disposal - the transports;

- Prisoner arrival;

- Prisoners as labor force;

- Types of prisoners:

- Drunks;

- Criminals;

- Politicals:

- People's Will terrorists;

- Right Socialist-Revolutionaries;

- Maximalists;

- Bolsheviks;

- Latvian communists;

- Duma deputies;

- Finnish judges;

- Soldiers;

- Armenians;

- Azeris;

- Jews;

- Administrative exiles;

- Exile Settlers.

III. Types of prisons:

- Hard-labor prisons;

- Temporary hard-labor prisons;

- Corrective-labor sections;

- Temporary corrective-labor sections;

- Transit prisons;

- Provincial prisons;

- District prisons;

- Women's prison sections;

- Special prisons;

- St. Petersburg Debtors' Prison;

- St. Petersburg Preliminary Detention

Facility;

- Investigation prisons;

- Alekseyevskiy Ravelin (Peter-and-Paul

Fortress);

- Prison hospitals;

- Camps for juvenile criminals;

- Naval floating prisons;

- Army disciplinary battalions;

- Army disciplinary units.

IV. The prison censorship regime -

who was authorized to censor the inmates' correspondence, and under what

circumstances:

- Superior court prosecutors;

- Superior deputy court prosecutors;

- District court prosecutors;

- District court deputy prosecutors

"supervising inquiries into State crimes;"

- District court deputy prosecutors;

- Court investigators;

- Assistant court investigators;

- Bankruptcy boards;

- Prison wardens;

- Acting and deputy wardens;

- Building wardens;

- Deputy warden office chiefs;

- Duty wardens;

- Chain-gang supervisors.

V. The "paper battle."

- Inmate and outsider efforts to

circumvent censorship:

- Euphemisms;

- Writing inside the envelope;

- Denial of information about the

sender:

- Location - riding the rails to

avoid detection;

- Omitting the return address on

registered mail;

- Typing to avoid identification by

handwriting;

- "Trust;"

- Efforts by the authorities to thwart

them:

- Chemical washes;

- Stamp removal or destruction;

- Tracking envelope contents;

- The power to issue or confiscate;

- Intentional mail delays;

- Cell searches;

- Cell and building changes.

VI. Types of mail allowed to

convicts, and postal usages:

- Stamp sales at prison commissaries;

- Correspondence abroad;

- Limits on frequency of

correspondence;

- Writing in the third person;

- Receiving mail - no restrictions;

- Money restrictions;

- Forwarded money mail;

- Money orders from abroad;

- Money orders between prisoners;

- Money-receipt notification forms;

- Domestic registered letters;

- Registered mail abroad;

- Reply-paid postcards;

- Address inquiry;

- Wrongly-addressed mail;

- Forwarded mail;

- Postage-due mail;

- Package mail;

- Telegrams;

- Correspondence between prisoners;

- Correspondence between prisoners and

exiles.

VII. The aftermath - prisons, camps

and courts in the early Soviet period:

- Fontanka, 16;

- Russian Civil War;

- Wardens into commissars;

- "Politicals"

in the Soviet era;

- Children of Imperial-period

politicals;

- The Soviet GULAG.

Bibliography*

- Adams, Bruce F., The Politics of

Punishment. Prison Reform in Russia 1863-1917, Northern Illinois

University Press, DeKalb, 1996.

- Braginskiy, M.A. (ed.),

Nerchinskaya katorga (Hard Labor in the Nerchinsk Region). Sbornik

Nerchinskogo zemlyachestva. Izd-vo Vsesoyuznogo obshchestva politkatorzhan

i ssyl'no-poselentsev, Moscow, 1933.

- Dobrinskaya, L.B. (comp.), Uzniki

Shlissel'burgskoy kreposti (Prisoners of Shlissel'burg Fortress), Lenizdat,

Leningrad, 1978.

- Galvazin, Sergey, Okhrannyye

struktury Rossiyskoy Imperii. Formirovaniye apparata, analiz operativnoy

praktiki (The Security Structures of the Russian Empire. The Formation of

Its Staff and an Analysis of Its Operational Procedures). Kollektsiya "Sovershenno

Sekretno," Moscow, 2001.

- Gavrilov, S., Russkiya tyur'my po

otchetam Glavnago Tyuremnago Upravleniya za 1903-1909 gody (Russian

Prisons from the Reports of the Main Prison Administration for 1903-1909),

Yuridicheskiy Vyestnik 2, 1913, pp. [241]-255.

- Gernet, M.N., Istoriya tsarskoy

tyur'my (History of the Tsarist Prison System), 5 vols, Moscow, 1963.

- Kennan, George, Siberia and the

Exile System, (2 vols.), The Century Company, New York, 1891.

- Kokovtsov, V.N. & S.V. Rukhlov

(comp.), Sistematicheskiy sbornik uzakoneniy i rasporyazheniy po

tyuremnoy chasti (Systematic Handbook of Laws and Instructions Concerning

the Prison Department), 2-e izd., Tipografiya I.N. Skorokhodova, St.

Petersburg, 1894.

- Leonidova, K.S. (comp.), Na

katorzhnom ostrove (On the Hard-Labor Island), Lenizdat, Leningrad, 1966.

- Margolis, A.D., Tyur'ma i ssylka v

imperatorskoy Rossii. Issledovaniya i arkhivnyye nakhodki (Prison and

Exile in Imperial Russia. Research and Archival Discoveries), Izd-va

Lanterna i Vita, Moscow, 1995.

- Reent, Yu.A., Obshchaya i

politicheskaya politsiya Rossii (1900-1917 gg.) (The Regular and Political

Police of Russia), "Uzoroch'ye," Ryazan', 2001.

- Skipton, David M. and P.A. Michalove,

Postal Censorship in Imperial Russia, 2 vols., John Otten, Champaign,

IL, 1987.

- Timofeyev, V.G.,

Ugolovno-ispolnitel'naya sistema Rossii: tsifry, fakty i sobytiya,

(Russia's Criminal and Executive System: Facts, Figures and Events),

Ministerstvo obrazovaniya Rossiyskoy Federatsii, Chuvashskiy

gosudarstvennyy universitet im. I.N. Ul'yanova, Cheboksary, 1999.

* This is a selective listing of the books

consulted during research for this exhibit. The full bibliography runs to 10

pages, and can be supplied upon request.

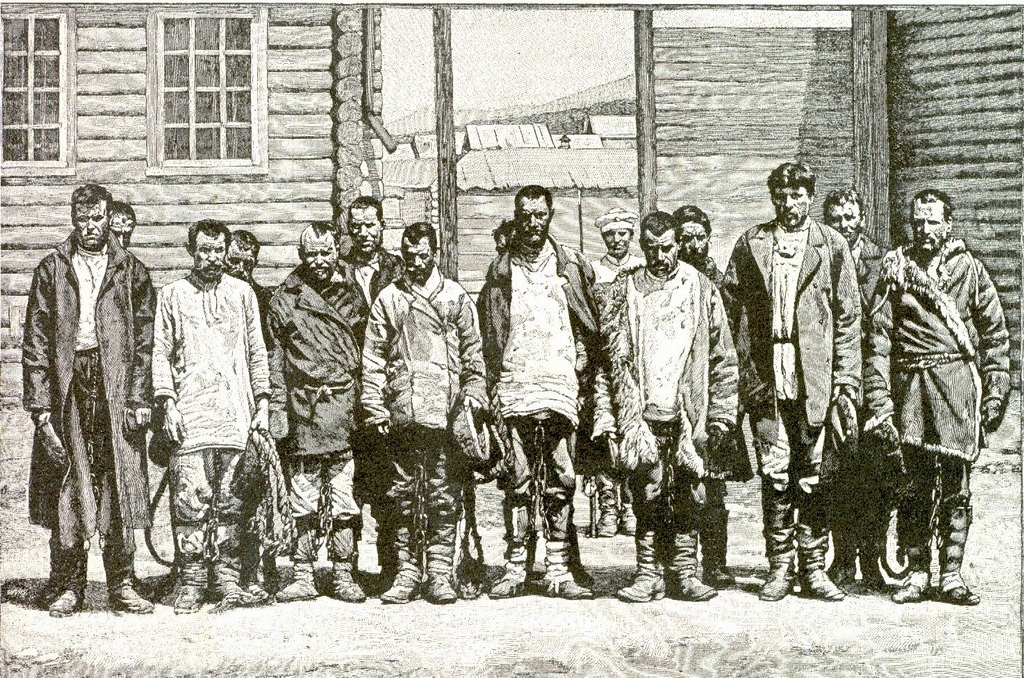

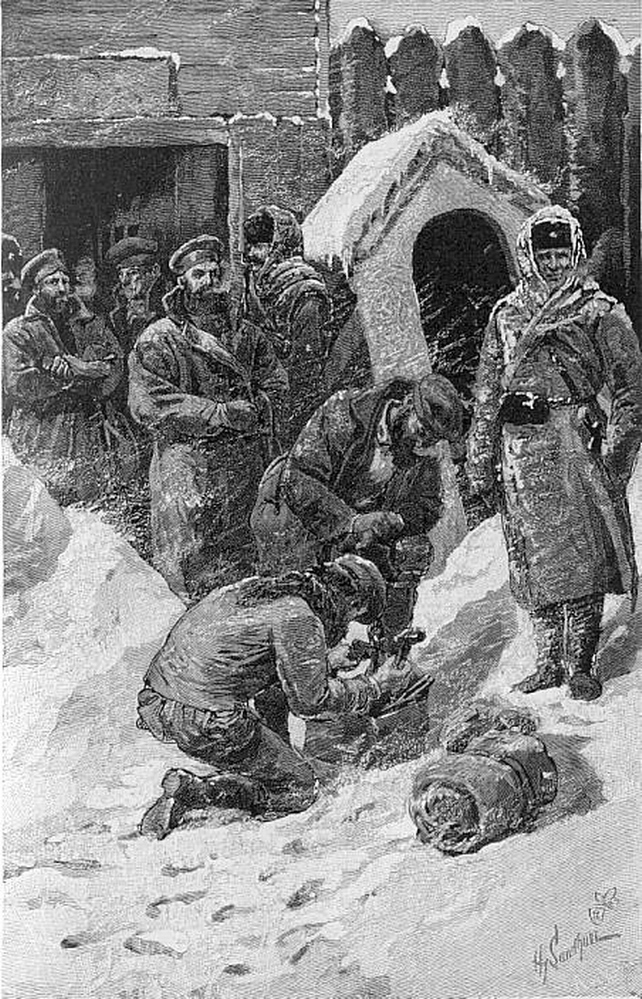

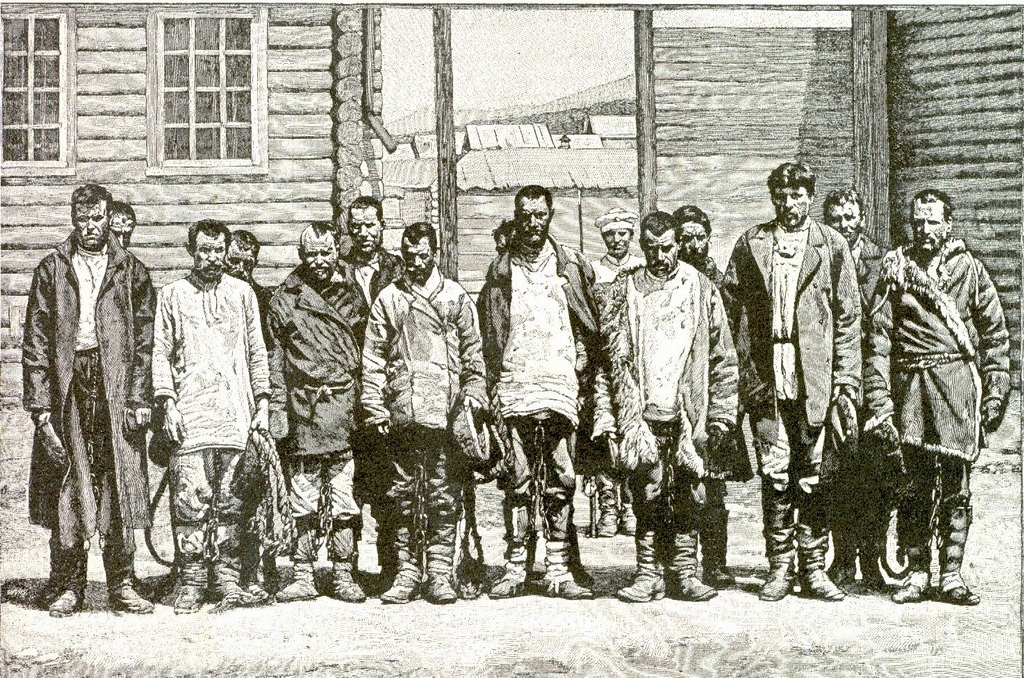

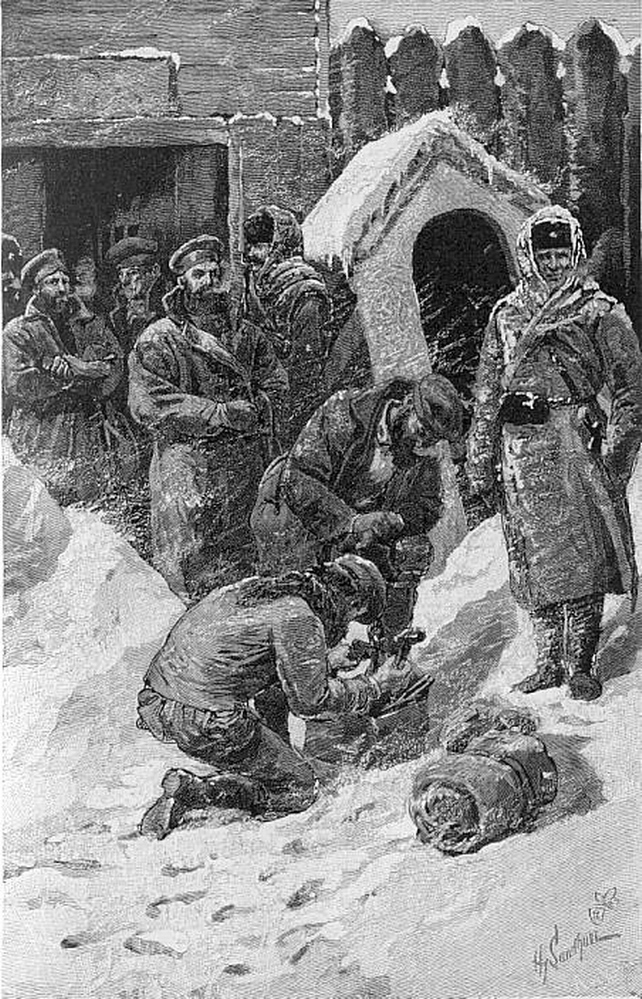

(Picture from Kennan, Siberia and the Exile System, vol. 2, p. 269.)

Endnotes:

[1] The "Judas Hole" refers to the peephole in the doors of the cells. It

enabled the warders to check on a prisoner to see if he or she was

conforming to prison regulations on behavior. A look through the hole at the

"wrong" time would betray the inmate, hence the name.

[2] Margolis, A.D., Tyur'ma i ssylka v imperatorskoi Rossii, p. 7.

[3] Trotsky, The Year 1905, accessed at http://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/works/1905/ch28.htm

on 8 October 2003.

[4] Luppov, Politicheskaya ssylka v Vyatskiy kray, pp. 83, 125.

[5] Skobennikov, M.V. Frunze (Arseniy) na katorge i v ssylke, p. 253.

[6] Lur'ye, O nekotorykh netochnostyakh, p. 139.

[7] Rumyantsev, Kamenev Lev Borisovich, accessed at http://hronos.km.ru/biograf/tomski.html

on 29 April 2005.

[8] Rumyantsev, Kosior Stanislav Vikent'evich, accessed at http://hronos.km.ru/biograf/tomski.html

on 29 April 2005.

[9] Vinogradov-Yagodin, Iz zhizni V.V. Kuybysheva, in Katorga i

ssylka No. 1, 1935, pp. 25, 33, 35.

[10] Diyenko, Razvedka i kontrrazvedka v litsakh, p. 279.

[11] Rumyantsev, Sergo Ordzhonikidze, accessed at http://hronos.km.ru/biograf/tomski.html

on 29 April 2005.

[12] Rumyantsev, Rudzutak Yan Ernestovich, accessed at http://hronos.km.ru/biograf/tomski.html

on 29 April 2005.

[13] Rumyantsev, Rykov Aleksey Ivanovich, accessed at http://hronos.km.ru/biograf/tomski.html

on 29 April 2005.

[14] Vinogradov-Yagodin, Iz zhizni V.V. Kuybysheva, p. 35.

[15] Rumyantsev, Tomskiy Mikhail Pavlovich, accessed at http://hronos.km.ru/biograf/tomski.html

on 29 April 2005.

[16] Diyenko, Razvedka i kontrrazvedka v litsakh, p. 489.

[17] Diyenko, Razvedka i kontrrazvedka v litsakh, p. 102.

[18] These reflect the sentences they received. It should be noted that all

of those who were sentenced to internal exile usually sat first in a prison

somewhere awaiting trial. Unless otherwise specified, these data were

extracted from Ivkin (comp.), Gosudarstvennaya vlast' SSSR: Vysshiye

organy vlasti i ikh rukovoditeli, 1923-1991. (Istoriko-biograficheskiy

spravochnik). For Yagoda, see also Diyenko, Razvedka i kontrrazvedka

v litsakh, p. 573.

[19] Vilenskiy-Sibiryakov, Dva yubileya. Dekabristy - Revolyutsiya 1905

goda

[20] Koz'min, Po povodu novogo izdaniya sochineniy D.I. Pisareva, in

Katorga i ssylka No. 1, 1935, 136.

[21] Luppov, Politicheskaya ssylka v Vyatskiy kray, p. 155.

[22] Druskin, Pis'mo v redaktsiyu, ko vsem uchastnikam revolyutsionnogo

dvizheniya, pp. 158-159.

|

|